Georgian Protests In Tbilisi Continue Amid Smoldering Anti-Russian Sentiment

Published 2019-07-01

Demonstrators crowded outside Georgia’s parliament building in Tbilisi throughout last week as protests continued over Russian involvement in Georgian internal affairs. The protests started on June 20th over the controversial visit of Sergei Gavrilov, a sitting member of the Russian government. Gavrilov opened an assembly session between Orthodox Christian lawmakers at the Georgian parliament and drew the ire of Georgian opposition leaders by sitting in the speaker’s seat and addressing representatives in Russian. Violence erupted when riot police tried to dispel the crowds with tear gas and rubber bullets and arrested protesters. Estimates vary but officials reported over 300 arrests and 250 injuries—including two people who lost their eyesight.

The Russian government was quick to put economic pressure on Georgia in retaliation for what it calls “russophobic hysteria”. It declared a ban on Russian flights to Georgia starting on July 8th and announced tighter restrictions on Georgian wine imports. The wine industry and the tourism sector are two of the most important components of Georgia’s economy. Russia is by far the largest market for Georgian exports and Russian tourists drive tourism in Georgia. The Russian government instituted similar punitive measures following the 2008 war with Georgia over the disputed territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, both of which Russia currently occupies.

The signs demonstrators carry reveal the degree to which the 2008 war soured relations between the two countries. Protesters hold signs that read “Russia is an Occupier” and pass out stickers that read “20%“—the percentage of the Georgian land that protesters consider occupied by Russia. During the conflict Russia supported the separatist movement in South Ossetia. Georgia sent troops to reclaim the territory in the autonomous region, but the Russian military repelled the troops and marched further into Georgian lands. Today there is still a Russian military presence in these disputed lands.

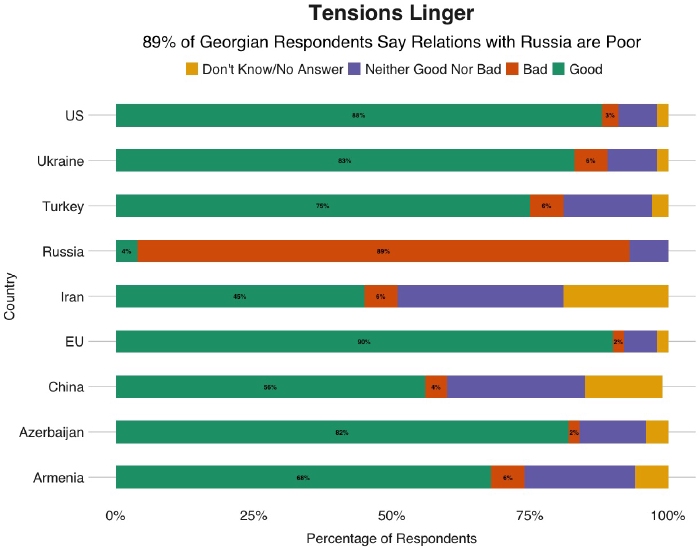

Resentment towards Russia over the conflict is pervasive. In a recent survey, 86% of Georgians said that there has been Russian aggression towards Georgia since 2008. 89% said that the current state of the relationship between the two countries is bad. Many consider it inevitable that Georgia’s unabashedly pro-Western outlook will rub against Russia’s political meddlesomeness and create tension. Since the Rose Revolution in 2003, which marked the end of Soviet-era leadership in the country, Georgian leaders pursued a pro-European foreign policy and openly stated their goal of European integration. EU flags are ubiquitous in the streets of Tbilisi, and American flags are common among the throng of protesters.

It looks as though further integration with Europe is inevitable. Georgians and European leaders alike consider the construction of a major container port in Anaklia, a city on the Black Sea, as yet another crucial step in Georgia’s progression towards full European integration. The massive container port, funded by European as well as American and Chinese investors, will open up a large trading corridor between China and Europe that flows directly through Georgia. It will give further weight to a future bid for EU ascendancy that Georgians overwhelmingly support.

The port will open up Western markets for Georgian goods, which will make the country less reliant on Russia for trade and less susceptible to its economic manipulations. Georgian and European financial backers of the project also point to another advantage: the venture raises the cost of Russian interference in Georgian affairs. The sight of protesters setting fire to pictures of Vladimir Putin under billowing EU flags in front of parliament is a fitting symbol of the country’s trajectory.