Gdańsk Is Again the Center of Controversy in Poland

Published 2019-03-15

The city of Gdańsk is used to controversy. In 1939, the Battle of Westerplatte marked one of the first battles of WWII, and occurred in the harbor of the Free City of Danzig. Once the war ended in 1945, ethnic Germans were expelled and Gdańsk joined the modern Third Polish Republic. In a pivotal historical moment during the 1980’s, the city became the birthplace of Solidarity, the first Eastern bloc trade union not controlled by a communist party. The Solidarity movement was a harbinger of the Soviet collapse, and helped bring an end to communism in Poland. Today, Gdańsk continues to be the center of events that reflect the zeitgeist of the nation. This time, the future looks grim.

In 2015, the Law and Justice party (known as PIS) completed a feat no party accomplished since the fall of communism in Poland: it won a parliamentary election with an outright majority. Under Jarosław Kaczyński’s defacto leadership, PIS ushered into the mainstream a political agenda that is at once socially conservative, economically interventionist, and euro-skeptic. Politics came into contact with everyday Polish life to an extent not seen since the fall of communism.

Gdańsk is again a microcosm of Poland, this time as an example of how far the government reaches into Polish affairs. In 2017, a new Museum of the Second World War was set to open. It’s director had a unique vision for the museum, and constructed its exhibits to avoid seeing the conflict through a nationalist lens. This drew the ire of the ruling party. For PIS, the global narrative, told through the multiple perspectives of those who experienced it, detracted from Poland’s suffering during the war. It did not help that Donald Tusk, the former prime minister of Poland and PIS’ political nemesis, initiated the museum’s creation.

Once PIS took power in 2015, they acted quickly. Despite the outcry from many high-profile historians, the Minister of Culture urged the museum “to present the Polish point of view” and accused the museum’s creators of promoting “pseudouniversalism” over a Polish narrative. They removed the museum’s director and replaced him with one more sympathetic to Polish suffering.

The controversy surrounding the museum not only reflects a greater intolerance toward historical realities PIS deems unsavory, but also a greater willingness to flout political norms to repress them. The museum foreshadowed the infamous Holocaust Speech law which in 2018 criminalized suggesting Polish complicity in the Holocaust, punishable by up to three years in prison. After international uproar, the government amended the legislation and removed the criminal penalty.

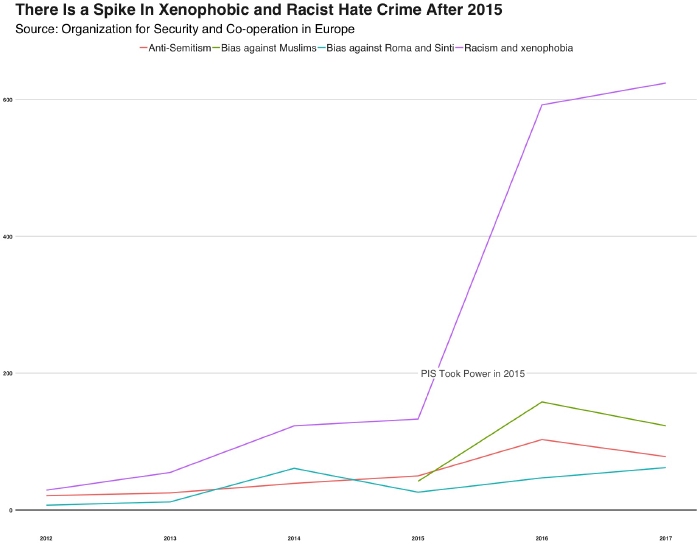

Two years since the museum’s opening, Gdańsk is again the center of national discord. In January of this year, an attacker assassinated the mayor of the city, Paweł Adamowicz. After stabbing the mayor during a charity event, the attacker stormed the microphone to claim that PIS’ political rival, Civic Platform (PO), wrongly imprisoned and tortured him. The event is a culmination of increasing rates of xenophobic and racist hate crime in Poland. It underscores the violence simmering below the surface in a time of political polarization, with spiteful rhetoric circulated by the highest levels of government.

Adamowicz was known for his progressive stances on various issues. He supported LGBT rights, recognized minority groups including the Kashubian population around Gdańsk, and welcomed refugees. This plurality of progressive views flew in the face of PIS’s staunch conservatism, and as a result Adamowicz was the target of hateful speech. A nationalist youth group printed fake death certificates for Adamowicz and others as a result of his pro-refugee views, and only days before his murder the charity event Adamowicz attended was the subject of an anti-Semitic satire broadcast on live television. What makes his murder all the more tragic is the fact that Adamowicz was part of the original workers’ strikes in Gdańsk that prompted the communist party to meet with Solidarity in the 1980’s.

Just last month, in the wake of memorial events celebrating Adamowicz, protestors toppled a memorial to a different controversial figure. A Gdańsk statue of Henryk Jankowski, a Catholic priest celebrated for his support of Solidarity, was the focal point of a contentious issue concerning recent allegations of pedophilia and child rape among Catholic priests. Reports accusing Polish clergy members roiled the religious nation, and Jankowski’s legacy came under fire.

The priest was a divisive figure before he died in 2010. During the 1990’s and 2000’s he espoused right-wing and euro-skeptic views that today are hallmarks of the ruling party. He also vocalized anti-Semitic views. As recent reports revealed Jankowski’s complicity in pedophilia, protestors toppled the statue in Gdańsk, but shipyard workers propped it up. Finally, city councilors voted to remove the statue for good.

The issue underscores another controversy central to modern Poland. As sexual abuse allegations embroil the Catholic church, PIS’s alignment with the institution further alienates PO and other progressive voices in the country. Intimately tied with this religious tension are reproductive issues. In 2016, women in all major Polish cities including Gdańsk dressed in black and protested in the streets against PIS’s tightening abortion laws. The memory of these protests and the uproar that followed among PIS supporters when the party abandoned its plan is still fresh in the nation’s consciousness.

Gdańsk has a tumultuous history of political unrest. It was the center of contentious events at pivotal moments in the nation’s history, and served as a window through which Poles and the rest of the world saw the country’s future. If the city continues to portend the nation’s future, it appears to be one defined by political division, simmering violence and historical censorship.