For Container Shipping, A US-China Trade Deal Might Not Be Enough

Published 2019-03-31

As US-China trade negotiations extend another month, container shipping companies are anxious to see the two powers reach a deal. The hero of globalization, container shipping fuels global economic growth by transporting a wide array of items across the world, including consumer goods and industrial items like heavy machinery. Container vessels transport 90% of the world’s non-bulk cargo, making them the lifeblood of world trade.

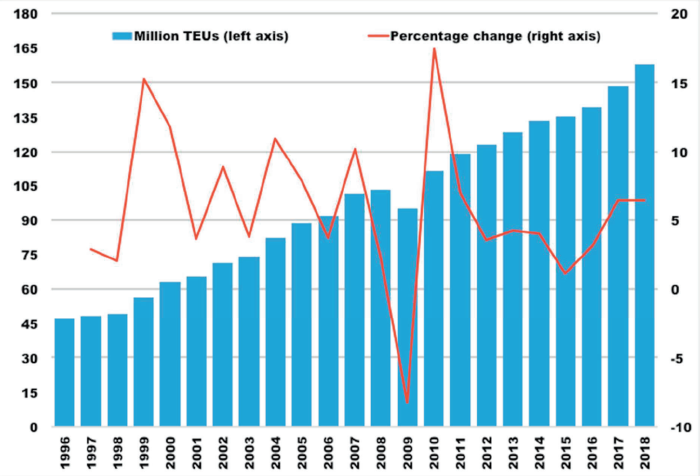

While container volume continues to grow, it has not returned to the growth levels it achieved before the financial collapse. Before 2009, container shipping saw around 8% annual growth. Since 2009, year over year volume increased less than 5%. Shipping giants like Maersk and COSCO hope a US-China trade deal will spark demand. However, the industry faces systemic problems that a favorable trade deal may be unable to ameliorate.

Transporting cargo by ocean is the most fuel-efficient way of moving goods, but the industry is at the mercy of global oil prices. By some estimates, fuel costs constitute about 60% of total ship operating costs, depending on the vessel type. For modern container vessels, which now rival oil tankers as the largest vessels on the seas, a typical ship could use over 200 tons of fuel a day. Though bunker fuel prices are volatile, an average cost is about $550/ton. At these rates, a 28-day journey across the Pacific could cost over $3.3 million dollars.

Further complicating fuels costs are new regulations passed by the International Maritime Organization to curb sulfur emissions. Container ships rely on heavy fuel oil. The crude oil contains high sulfur oxide content which, after combustion in ship engines, constitute ship emissions that are harmful to the environment and to human health. Set to take place in 2020, a new IMO regulation will limit sulfur levels in fuel oil used onboard vessels to 0.5% mass by mass. Shipping analysts estimate that this regulation will drive up fuel costs by a third.

Recent high-profile accidents also increase insurance costs for the oceangoing monoliths. In the past four months, four major fires occurred onboard container vessels. The latest took place in March. A combination container and automobile carrier caught fire and sank off the French coast, destroying over 2000 luxury Audi and Porsche vehicles.

Insuring these vessels is big business. Representatives from one of the largest logistics insurers, TT Club, stated that on average there is a fire at sea every 2 months, and that claims often exceed $500 million annually. To shave costs, ship operators now load more cargo on bigger ships and make fewer port calls. The likelihood of an accident increases as shipping containers stack higher. As ships grow, so do insurance costs.

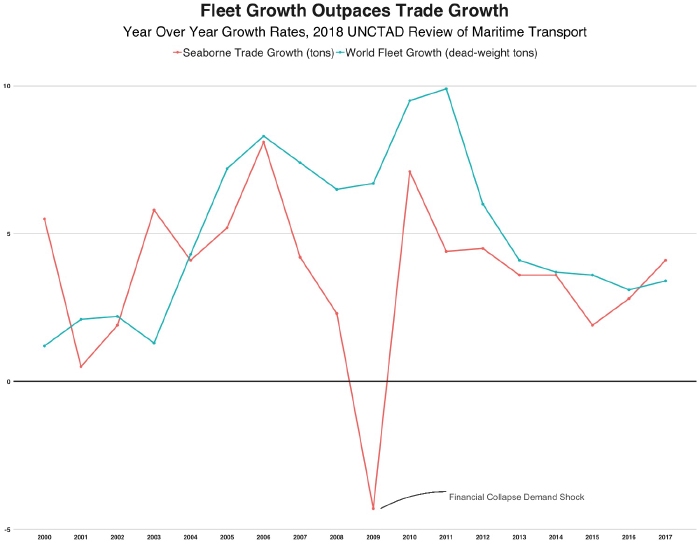

Today container shipping suffers from overcapacity. Before 2009, ship construction intensified to keep pace with the precipitous rise in container demand. It takes time to build the leviathan vessels, and when seaborne trade contracted after 2008, growth in the world fleet could not respond. Supply outstripped demand, and a glut in container capacity emerged. Trade wars and slowing global growth make container demand unlikely to stay above supply in the coming years.

The response to the capacity surplus by the world’s largest ship owners is varied. Some operators chose to build larger ships to transport larger loads in fewer trips. This has led to disruptions in the global supply chain, and delayed order fulfillments resulting from less-frequent calls on important liner ship routes. Many cargo carriers chose to merge together to absorb some of the burdensome costs involved with maintaining shipping routes and to exploit operational efficiencies to ease the burden of rising costs. The result is greater consolidation in the container shipping market. In January of 2018, the top 15 carriers controlled 70% of global fleet capacity, but by June of the same year the top 10 carriers controlled the same 70% of global capacity.

Demand for container shipping is intertwined with the state of the global economy. Both the IMF and the World Bank adjusted their forecasts for global growth in 2019. Central to this global deceleration is China’s economic slowdown. China’s economy grew at its slowest pace last year in nearly thirty years. This spells trouble for container shipping. Shares in the largest container shipping company, Moller-Maersk, nosedived last month when a representative warned investors that trade war uncertainties were taking their toll. This signals a grim Q1 earnings report for 2019, as the company comes off a fourth quarter loss in 2018 of $34 million. A trade deal may improve short-term demand forecasts, but the industry suffers from a host of problems that could plague shipping for years to come.