In Poland, Overlapping Anniversaries Highlight Political Divisions

Published 2019-06-10

Last week was a momentous one for Poles. Tuesday marked the 30th anniversary of the country’s first free elections after communism and Sunday the 40th anniversary of the first visit of John Paul II—the first Polish pope—to Poland. Commemoration celebrations took place throughout Poland for both events. Both are essential pieces of Poland’s break with its communist past. In divisive times, however, attendance at each commemoration event is highly politicized.

In keeping with their agenda characterized by cultural uniformity and traditional values, the Polish government—headed by the de facto leader Jarosław Kaczyński—focused on the memorial of John Paul II’s visit. Government leaders did not head to Gdańsk, the site of the Solidarity protests which initiated the dissolution of communism in Poland, to attend anniversary events. The decision underscores the government’s vision for the country and highlights Kaczyński’s break with his own past.

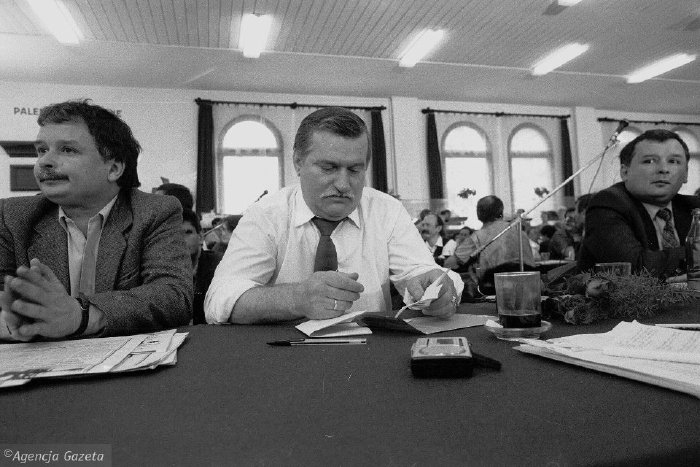

When Poland became the first Soviet state to institute semi-free elections in 1989, Jarosław Kaczyński and his twin brother Lech were middle-ranking members of the Solidarity trade union. Both achieved their initial fame by participating in the round-table talks in 1989 which initiated the free elections. The twin brothers were able to sustain their fame, however, by criticizing Solidarity leadership of the newly independent Poland. They claimed Lech Wałesa, the celebrated leader of the trade union, and other Solidarity leaders favored cooperation with the communists which betrayed Poland’s transition to democracy.

Jarosław’s views received a wider audience in 2010 when his brother Lech died in the plane crash near Smolensk that killed several members of the Polish government. Without Lech, whose reserved demeanor tempered his brother’s rancorous approach to politics, Jarosław’s views veered further to the extreme. His brother’s death thrust him into the limelight, and he used the media attention to perpetuate conspiracy theories about his brother’s crash, denounce the liberal elite who supposedly sold Poland to the communists, and criticize Poland’s relationship with the EU.

Like any talented consolidator of power, Kaczyński capitalized on the opportunity that his brother’s death afforded him to bolster his own influence in Polish politics. He also used the opportunity to marginalize his political enemies, namely Lech Wałesa. Wałesa is an outspoken critic of Kaczyński. However, Kaczyński has been able to successfully weaponize populist politics and defaming conspiracy theories to diminish Wałesa’s role in Polish politics. Kaczyński accused Wałesa of acting as a communist agent and for installing liberal intellectuals into power once Poland regained independence. While still an important symbolic figure, Wałesa is now largely cast aside from current Polish politics. More importantly, Kaczyński’s conservative, nationalist agenda supplanted Wałesa’s vision for a liberal, western-oriented democracy in mainstream Polish politics.

In a country with a history rich with symbols, attendance at memorial events is in turn symbolic. In a country with great political division, participation is not only an act of commemoration but also an act of allegiance. The government’s decision to concentrate on the memorial of John Paul II’s speech over the anniversary of free elections emblemizes its vision for a culturally homogenous, nationalist Poland. The decision also exemplifies the lengths Kaczyński went—after assuring his own fame and power—to sever his ties with Solidarity and to turn his back on the pro-democracy ideals it represented.