Chinese Language Criterion Cinema

United Kingdom: 181. Japan: 346. France: 374. US: 593. As of June 29th 2020, these are the number of films from each country of the 2123 films available in the Criterion collection. This means almost 30% of films in the collection are American. What about the most populous country in the world? Taking together ALL Chinese-language films (including Taiwanese, Hong Kongese and Chinese) there are a total of 33 films, comprising about 1.5% of the total. Even for film buffs, Chinese-language films are thin on the ground.

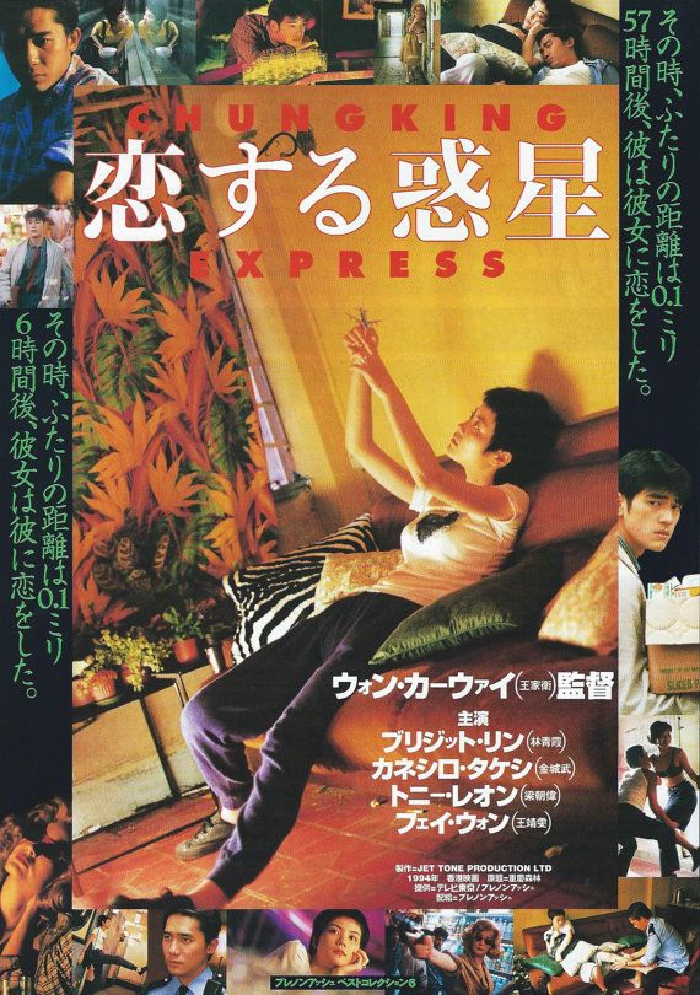

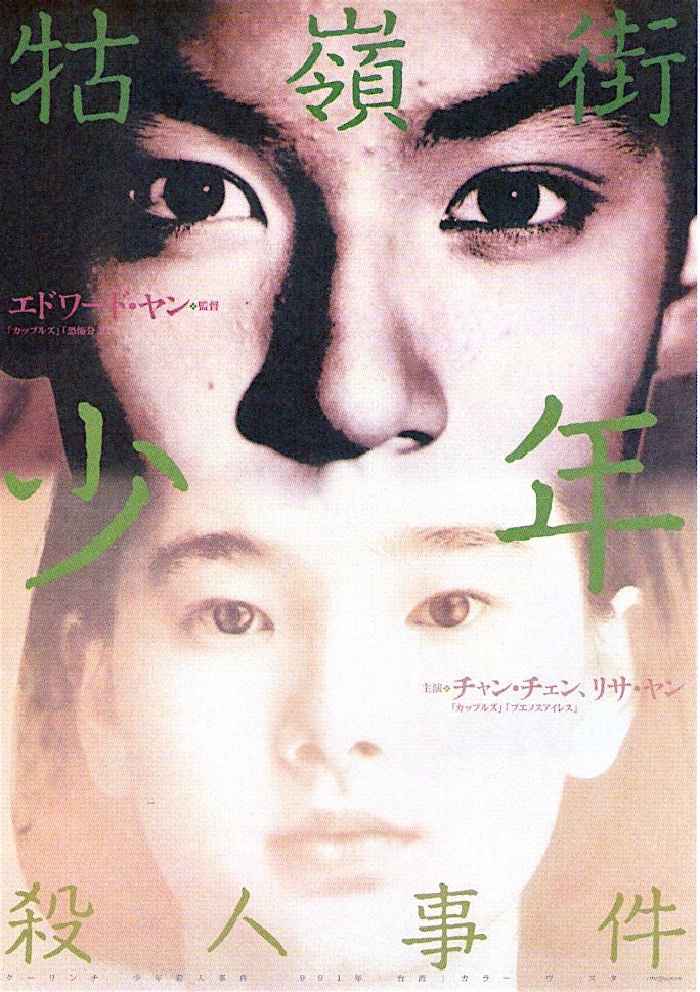

This makes the Chinese-language films available all the more precious. I recently watched Chunking Express, a 1991 film set in Hong Kong directed by Wang Kar-Wai, and A Brighter Summer Day, a 1991 film set in Taiwan directed by Edward Yang. Though they were released around the same time and are among the rare celebrated films in the Chinese-language film cannon, that is where the similarities end.

If memories could be canned, would they also have expiry dates?

Watching Chungking Express means watching two films for the price of one. It features two stories about two different relationships, but with some broad similarities. Both men in each story are cops and each is struggling to get over a woman from a previous relationship. The couples never meet each other, but the first story transitions to the second at a fast food express restaurant that helps give the film its name.

The man in the first story is a lovesick young man. He meets a woman in a bar whose identity is kept hidden and who wears an iconic blonde wig. Her character is a noir archetype— she is mysterious, elusive, and deeply engaged in shady underworld dealings. In a memorable scene she runs from some captors through the stalls in the Chungking mansions (responsible for the other half of the movie’s name). The chase scene features a jilted, cut-frame sequence that looks out of date today but at the time was a novel approach to film editing. Her strong-willed character contrasts the teenage cop’s boyish nature. The first mini-film revels in its own genre and gender-role bending, but the second mini-film switches tone completely.

The second half features a quirky worker at the fast-food restaurant named Faye. Her awkward disposition contrasts with the cop’s stoic demeanor. The cop’s old lover—a flight attendant—leaves him a letter with Faye, but instead of giving it to him she reads the letter, takes the keys from inside and sneaks into his apartment. She takes to cleaning the apartment while he is gone until one day he finds her in it.

They end up hitting it off, and just as the relationship starts to blossom, Faye doesn’t show up to their first date. Instead, she becomes a flight attendant and flies to California. They meet a over year later, and the cop reveals to her that he has not forgotten about her and has bought the fast food joint hoping he would see her again. In under 2 hours, Chungking Express manages to entwine a noir, a coming of age story, and a romance into a single film.

Does your memory stray…?

Yang’s 4-hour epic could not be more different in style. In contrast to Kar-wai’s jittery and experimental camerawork, Yang’s 4-hour epic is full of long single-frame shots. His style is austere and deliberate. He tends to focus on empty spaces, and when a character enters a shot there is a great deal of space surrounding them. He avoids close-ups and focuses on how the characters move through the vast background.

In direct contrast to Chungking Express, in which the entire focus of each mini film is on two characters, A Brighter Summer Day features an entire cast of characters. The main characters are Si’r and Ming, but the plot doesn’t revolve around them as much as it unfolds around them. Each time they appear it’s as if their trajectory just happens to cross paths with the main action of the plot. A memorable scene is when Ming and Si’r are walking by a shooting range, and the camera pans out to show that they on a collision course with members of a rival gang.

The rest of the cast is Shakespearean in breadth—it features a host of characters with their own fleshed out personalities and arcs. One of these characters is Cat, Si’r’s best friend. His short stature and high voice contrast his bellicose nature. When a rival gang accosts Si’r and Cat, Cat searches about for someone who can supply them weapons to exact revenge. However, Yang reveals that this isn’t Cat’s true nature. For one, he is a singer. The plot centers around several concerts, and at one of them he uses his high-pitched voice to sing an Elvis cover (the film title comes from lyrics of this song). Cat completes his arc as Si’r’s devout friend in a final scene as he tries in vain to send Si’r tapes while he is behind bars.

Another major character is Si’r’s father. His role emphasizes how the choices one generation makes burden the next generation. Si’r and his family have to deal with the stresses of growing up in Taiwan, away from the Chinese mainland that Si’r’s parents fled. Their societal status is diminished since Si’r’s father cannot continue to work in government and his mother cannot continue her work as a teacher.

Si’r’s father struggles to move up the social ladder and avoid trouble with the secret police mirror Sir’s struggles to fit in at his school. Si’r’s father bears interrogation by the Taiwanese authoritarian regime about his mainland connections while Si’r fends off the lure of gang involvement.

Si’r also succumbs to the same angry outbursts that get his father into trouble. In one scene Si’r’s father lashes out in anger at his wife in their bedroom for her lack of faith in him. This scene foreshadows the shocking ending of the film, when Si’r’s explosive anger completes his transformation from meek student to gang member to violent criminal.

The legacy of family is an important theme for the film and is completely absent in Chungking Express. None of the characters in Kar-wai’s film make any familial contact. They are loners in an anonymous metropolis, and the film emphasizes the characters’ transient presence. It’s no accident that two of the main characters are stewardesses: the characters are in motion, fleeing captors or flying to different places. In Brighter Summer Day, the characters are stuck in Taiwan with no ability to leave. In a small scene, Si’r’s mother mentions her desire to send her older sister to the U.S. for school. The older sister laughs at the ridiculousness of leaving the family when they are in such a precarious situation.

It’s not a coincidence that the scenes with Si’r’s many sisters are small and undeveloped. Yang’s film is the story of father and son. The female characters are relegated to the side, emphasizing the patriarchal nature of Taiwanese society in the 1960’s. In contrast, female characters are at the fore of *Chungking Express*—each of the stories star a fully-developed female lead.

While differences abound, an important similarity unites the two films. Each depicts a setting that is a confluence of cultural influences. Chungking Express’s Hong Kong setting speaks for itself. The city is a mélange of globalism, freewheeling individualism (until recently) and extreme capitalism. One of the first shots of the film is of the Chungking Mansions, a city in and of itself in which various ethnic minorities converge to sell their goods. The traces of globalism permeate every scene, from the main character’s blonde wig to the canned food in the gas station to the English-language karaoke bar. In a memorable scene, the two characters in first film speak to each other at first in Mandarin, then in English, and then in Cantonese. Chungking Express depicts a place where the process of cultural fusion is fully realized.

The Taiwan in A Brighter Summer Day is also at an intersection of historical influences. The local Taiwanese have a culture distinct from those newly immigrated from the Chinese mainland. Many of the families in the film live in houses abandoned by the Japanese after their occupation in the late 19th century and after their expulsion following WWII. In one scene, Si’r’s mother complains that the neighbors listen to Japanese music too loudly. At school, the boys play American sports like baseball and basketball and voraciously consume American pop music.

It’s interesting to note that in Chungking Express, these diverse cultural elements feel well integrated while in A Brighter Summer Day they feel distinct. In the former film, the fusion of cultures is so complete that the director feels no need to comment on any particular influence. However, this identity-building process is at the heart of the latter film. The decisions that this vulnerable generation of Taiwanese people must make, like to what extent to embrace cultural diversity, are burdensome and imbibed with meaning. It’s not a coincidence that two of the symbols of foreign cultures—the samurai sword and the baseball bat—are used for violent ends. Sir’s arc captures the tragedy of a younger generation struggling to belong.

The most striking similarity between the two films is that they each have an American pop song at their heart. In Chungking Express, California Dreamin by The Mamas & the Papas recurs throughout the film. It symbolizes the desire of the female lead in the second story to move and to change her surroundings, while also suggesting that her desire is just a fantasy and perhaps she doesn’t want to change. Elvis’s Are You Lonesome Tonight is at the heart of A Brighter Summer Day. It captures the romantic ache of adolescence, and its tenderness gives the movie a melancholic twinge given the tragic relationship at its center.

Given how disparate the two films and the directors’ styles are, I’ll never know why they are both lumped together as “Chinese-language” films. What I do know is that I will never listen to California Dreamin or Are You Lonesome Tonight the same way again.